This is a free sample from Chapter 1 of Modern C#: Developers’ Craft in the AI Era.

In this chapter, you’ll set up your development environment and explore the core mechanics of the .NET runtime and the C# type system. We won’t dwell on basic control flow like if/else statements and loops; instead, we’ll dive straight into the foundational concepts that truly matter. These concepts are essential for mastering the more advanced C# features covered later in this book.

1.1 The design philosophy

Before diving into syntax details, let’s build a big-picture mental model of C#.

Primarily OOP with FP features

C# is an object-oriented language that emphasizes encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism. Starting with C# 3.0, however, it incorporated many of the best ideas from functional programming:

| Functional feature | How C# supports it |

|---|---|

| Functions as values | Delegates and lambda expressions |

| Declarative data processing | LINQ query expressions |

| Immutable data structures | record, readonly struct, init accessors |

| Pattern matching | switch expressions, the is operator |

Terminology

In programming languages, an expression is typically “a piece of code that can be evaluated and produces a value.” A statement, on the other hand, performs an action and usually does not directly produce a value.

This is the OOP + FP hybrid design: C# combines the organizational power of object-oriented programming with the expressiveness of functional programming. Records, pattern matching, and LINQ—all covered later in this book—are key parts of this philosophy.

With that high-level overview in place, let’s move on to the type system.

Type safety: your first defense

C# is a strongly typed language with strict type rules:

- Static typing: A variable’s type is determined at compile time, and the compiler checks type errors before the program runs.

- Strong typing: Risky implicit conversions are not allowed. For example, you can’t assign a

doubledirectly to anint; you must cast explicitly.

The benefits are obvious: you catch problems early and avoid runtime errors. Many modern C# features (such as Nullable Reference Types) reinforce this safety net.

// The compiler prevents this unsafe operation.

double pi = 3.14159;

int rounded = pi; // ✗ Compile-time error: cannot implicitly convert

int rounded = (int)pi; // ✓ Explicit cast; you're choosing to truncateNote

In short: let the compiler catch bugs for you. Type safety, null safety, pattern matching, and record-based value equality all reduce surprises at runtime.

1.2 Quick start

This section walks you through creating the simplest possible .NET project and observing how it compiles and runs. For now, we’ll bypass full-featured IDEs in favor of the command-line interface (CLI). This is the best way to understand the .NET project structure and build pipeline—skills essential for automation.

Required tools

Before you begin, install the following:

- .NET 10 SDK (or later): required for building .NET applications.

- A development tool (IDE/editor). Pick what you’re comfortable with:

- Visual Studio 2026 Community: the most powerful Windows IDE for large and enterprise projects.

- Visual Studio Code: cross-platform (Windows/macOS/Linux), lightweight, and highly extensible—great if you like fast editing and a customizable workflow.

- JetBrains Rider: a cross-platform IDE (Windows/macOS/Linux); free for non-commercial use.

Your first .NET project

Forget File > New Project for a moment. Open a terminal (the commands below use Windows as an example) and follow these steps:

Step 1: Create a console app

dotnet new console --name HelloCSharpThis creates a C# console project named HelloCSharp from the default template. You’ll get a Program.cs file with a default entry point that contains just one line of code (excluding comments):

// See https://aka.ms/new-console-template for more information

Console.WriteLine("Hello, World!");Step 2: Enter the project directory

cd HelloCSharpStep 3: Run the app

dotnet runWhen you run dotnet run, the .NET SDK will restore missing components (restore packages), compile the project (build), and then execute it. You should see:

Hello, World!That process involves three commands and three responsibilities:

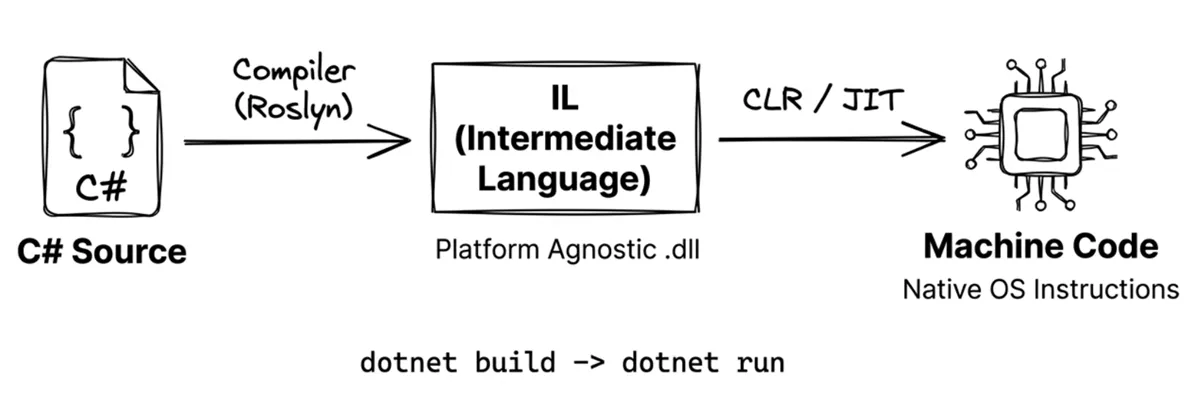

dotnet new: Generates the project file (.csproj) and source file (Program.cs) from a template.dotnet build: Compiles C# source into Intermediate Language (IL) and packages it into a.dllor.exe.dotnet run: Starts the .NET runtime (Common Language Runtime, CLR) to execute the compiled program.

What is IL (Intermediate Language)?

C# code is not compiled directly into machine code. Instead, it’s compiled into a platform-independent instruction set called IL. This allows the same compiled output to run on Windows, macOS, Linux, and more. At runtime, the .NET runtime (CLR) uses JIT (Just-In-Time) compilation to translate IL into native machine code for the current platform. For details, see the Microsoft documentation.

If you’d like to try writing and running the example using an IDE, see Microsoft’s tutorial: Create a .NET console application using Visual Studio.

Note

Modern C# projects typically enable top-level statements. That’s why

Program.csno longer contains the olderclass Program/static void Mainboilerplate—you just writeConsole.WriteLine("Hello, World!");directly.

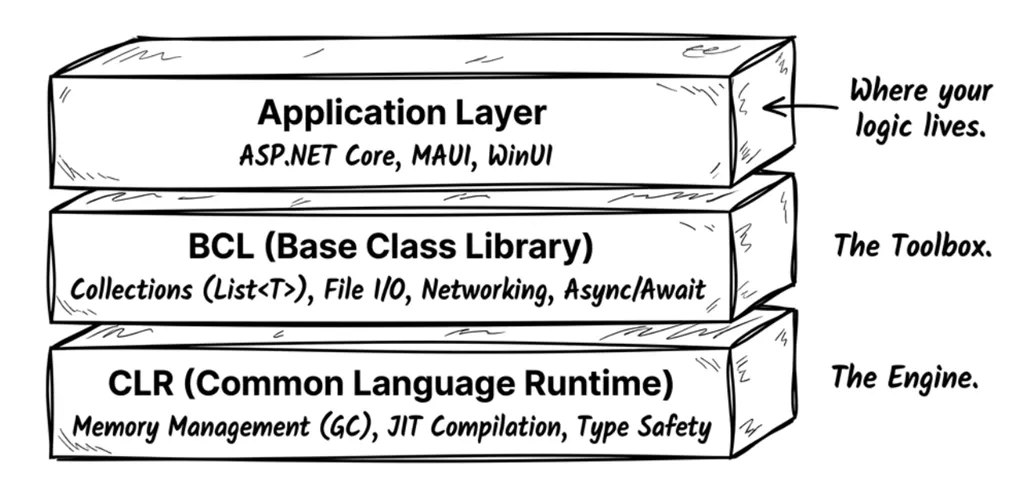

1.3 The .NET runtime architecture

When you type dotnet run, a carefully layered system goes to work behind the scenes. .NET uses a layered design that balances developer convenience with low-level performance control. At a high level, you can break the .NET runtime environment into three layers:

| Layer | Name | Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| Top | Application Layer | Application frameworks (ASP.NET, MAUI, WinUI, etc.) |

| Middle | BCL | Base Class Library (collections, I/O, networking, cryptography, etc.) |

| Bottom | CLR | Common Language Runtime (memory management, JIT compilation, exception handling) |

As shown below:

The CLR (Common Language Runtime) is the heart of .NET. It’s responsible for:

- Compiling IL into machine code (JIT compilation)

- Automatic memory management (garbage collection)

- Type-safety checks

- Exception handling

The BCL (Base Class Library) provides the everyday building blocks you use constantly:

- Collections (

List<T>,Dictionary<K,V>) - String processing and regular expressions

- File I/O and networking

- Asynchronous programming (

async/await)

The Application Layer contains higher-level frameworks for specific app types:

- ASP.NET Core: web apps and APIs

- MAUI: cross-platform mobile and desktop apps

- WinUI / WPF: Windows desktop apps

Cross-platform support

Modern .NET (since .NET 5) supports multiple platforms:

| Platform | Supported app types |

|---|---|

| Windows | Console, Web, desktop (WPF/WinUI), services |

| macOS | Console, Web, desktop (Mac Catalyst) |

| Linux | Console, Web, services |

| iOS / Android | Mobile apps (via MAUI) |

| Browser | WebAssembly (via Blazor) |

This means C# code can run on any of these platforms, provided it avoids platform-specific APIs.

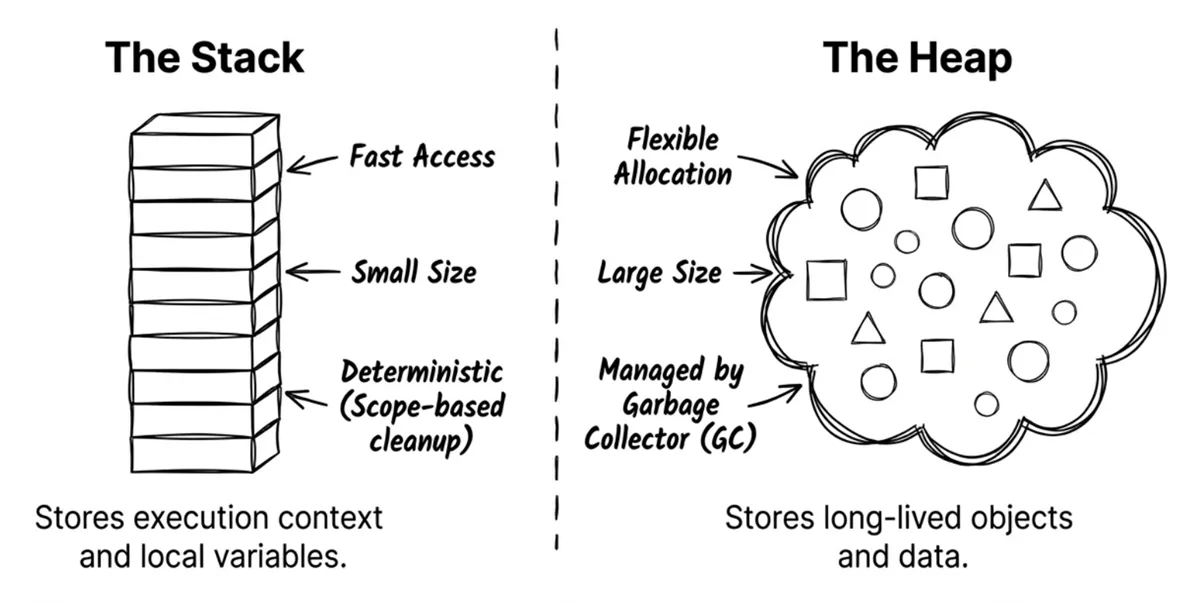

1.4 Stack and heap

Writing high-performance, bug-free code requires a solid understanding of memory allocation. Two foundational concepts are the stack and the heap.

An intuitive way to think about them:

-

The stack is like your physical desk:

- Limited space, but extremely fast access.

- Used for the work you’re doing right now (method calls and local variables).

- When the work is done (the method returns), the desk is cleared instantly.

-

The heap is like a warehouse:

- Very large, but slower to access.

- Used for long-lived data or large objects.

- When you’re done with an item, it doesn’t disappear immediately—it waits for the cleanup crew (the garbage collector) to reclaim it.

Both stack and heap are just regions of memory. We give them different names because they’re used differently.

The stack

-

Characteristics:

- Very fast: allocation and release are just pointer moves.

- Deterministic: variables are released automatically when they leave scope.

- Small: often just a few MB; exhausting it causes

StackOverflowException.

-

What it stores:

- Basic data for local variables.

- Method call context (parameters and call frames).

The heap

-

Characteristics:

- Slower: allocation requires finding enough contiguous space; deallocation relies on the garbage collector (GC).

- Flexible: large space, suitable for long-lived or variably sized data.

-

What it stores:

- Larger or longer-lived data, objects, and collections.

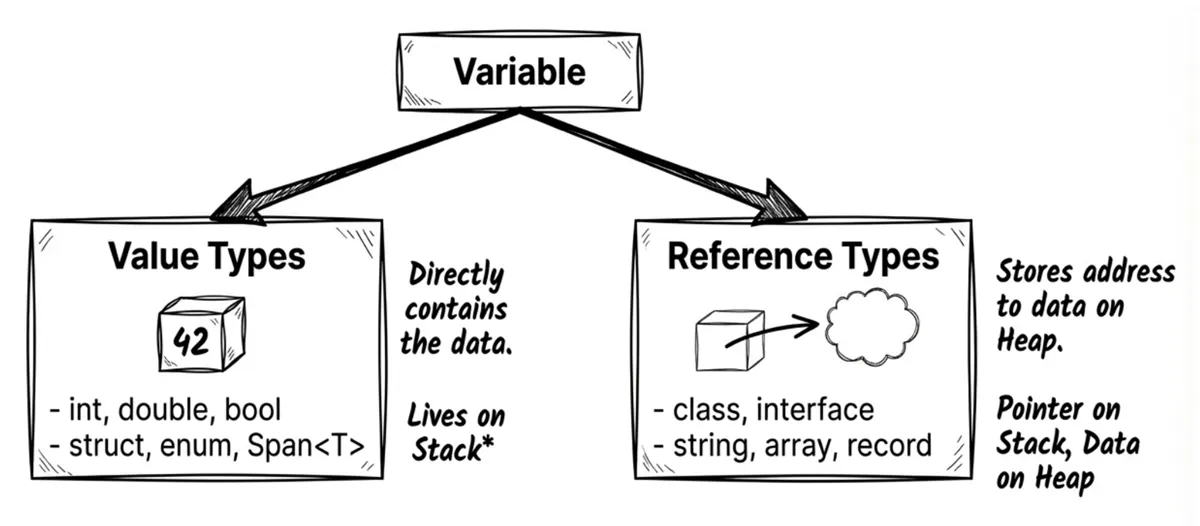

1.5 Value types and reference types

C# programs don’t run directly on the operating system; instead, they execute within a managed environment called the CLR (Common Language Runtime). The CLR has many responsibilities, such as managing memory, handling exceptions, and providing safety mechanisms. You don’t need to learn all the CLR internals right away. For now, remember these two key jobs:

- Managing type information

- Allocating and reclaiming memory (garbage collection)

When it comes to allocation, the CLR decides—based on a type’s characteristics and its actual usage—whether data ends up on the stack or on the heap. One important characteristic is C#’s two type categories: value types and reference types.

Value types

Value types include:

- All numeric types (

int,double,byte,decimal, …) bool,charenumstruct(includingDateTime,Guid,Span<T>)

Behavior characteristics:

- They contain the data directly.

- Assigning one to another variable copies the entire value (copy by value).

Think of it like photocopying a document. If you copy document A to a coworker (assignment), and your coworker writes on their copy (mutates their variable), it doesn’t affect your original.

Example:

int a = 10;

int b = a; // Copies 10 into b

b = 99; // Changing b does not affect a

Console.WriteLine(a); // Prints 10Line 3 changes b, but a remains unchanged because int is a value type.

Source code: DemoValueTypes

Reference types

Reference types include:

class(includingstring,object, and arrays[])interfacedelegate(delegates and events are covered in Chapter 8)record(a reference type by default; see Chapter 4)

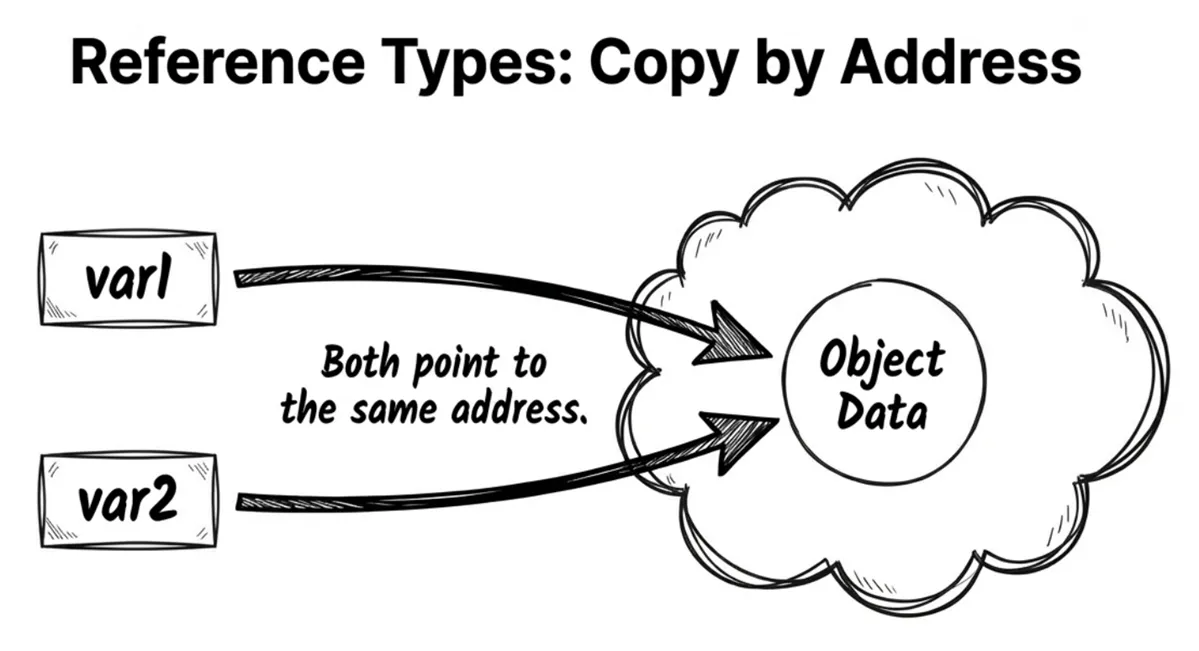

Behavior characteristics:

- They store a reference (a memory address) that points to an object on the heap.

- Assigning one to another variable copies only the reference, resulting in both variables pointing to the same object.

It’s like sharing a cloud-document link. You send your coworker the link (assignment). Both of you hold only the link (the reference), but the link points to the same underlying document (the object). If your coworker edits the document through the link, you’ll see the changes too.

Example:

var user1 = new User { Name = "Alice" };

var user2 = user1; // Copies the reference; user1 and user2 point to the same object

user2.Name = "Bob"; // Changing user2 affects user1

Console.WriteLine(user1.Name); // Prints BobSource code: DemoReferenceTypes

Ask AI: common type gotchas

Many bugs come from misunderstanding type categories (and interview questions love this topic). Try the following prompt with your AI tool to check your understanding:

Prompt

In C#, is

int[](an array of integers) a value type or a reference type? If it’s a reference type, but it containsintelements (value types), where are thoseintvalues stored—on the stack or on the heap? Explain the underlying memory layout.

Depending on the AI tool you use, answers may vary slightly. Here’s a simplified example answer:

AI Answer

int[]is an array, and arrays are reference types. Therefore, the entire array object (including all itsintelements) is stored on the heap, even thoughintitself is a value type.

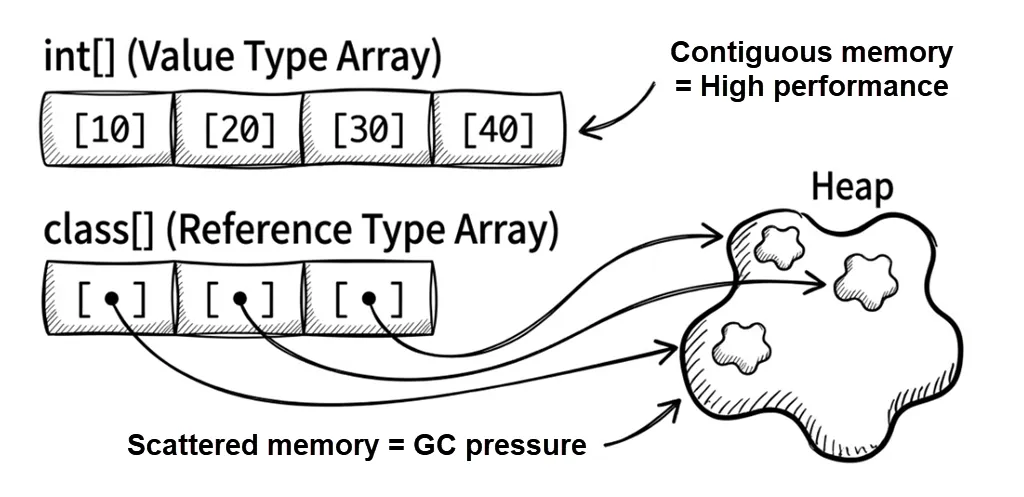

Array layout: value vs reference elements

Many developers believe an array is “always a contiguous block of memory,” but this is only partially true.

The underlying memory layout depends heavily on whether the element type is a value type or a reference type. This difference can affect performance (CPU cache locality) and garbage collection (GC) pressure. Let’s look at both cases from a memory-allocation perspective.

Arrays of value-type elements

Example:

long[] numbers = new long[3]; // Each long is 8 bytes

numbers[0] = 12345;

numbers[1] = 54321;

numbers[2] = 99999;On the heap, the CLR allocates a contiguous chunk of memory. The three long values are stored directly inside the array. Concretely:

- Array header: Includes metadata such as the array length.

- Contents: Stores the raw values (like

12345) packed tightly. - Result: One allocation; data is dense and cache-friendly.

An analogy: a row of lockers at the gym. Open locker #0 and your item (the value) is right there. Open locker #1 and the next item is right there too.

Arrays of reference-type elements

StringBuilder[] builders = new StringBuilder[3];

builders[0] = new StringBuilder("builder1");

builders[1] = new StringBuilder("builder2");

builders[2] = new StringBuilder("builder3");In this case, the array stores references, not the objects themselves:

- Array header: Includes metadata such as length.

- Contents: Stores references (addresses) to

StringBuilderobjects. - Actual objects: Allocated separately and scattered on the heap.

- Result: Multiple allocations (one for the array + one for each object), poorer locality, and higher access cost.

An analogy: a row of mailboxes. Mailbox #0 contains a note (a reference) saying “your package is in warehouse section B, shelf 3.” You then have to go to the warehouse (somewhere else on the heap) to retrieve the package (the object). If each note points to a different corner of the warehouse, you’ll waste significant time walking back and forth.

This leads to two important effects:

- Locality: value-type arrays store elements contiguously, so CPU cache hit rates tend to be higher.

- GC pressure: reference-type arrays often create many scattered objects, increasing garbage collector work.

Key takeaways for this section:

- Whether you’re using a value type or a reference type, data still has to live somewhere in memory.

- In most cases, local variables are allocated on the stack.

- Value-type variables typically store the actual data directly (often on the stack).

- Reference-type variables may live on the stack or heap (depending on context), but the variable’s value is a heap address that points to the actual object.

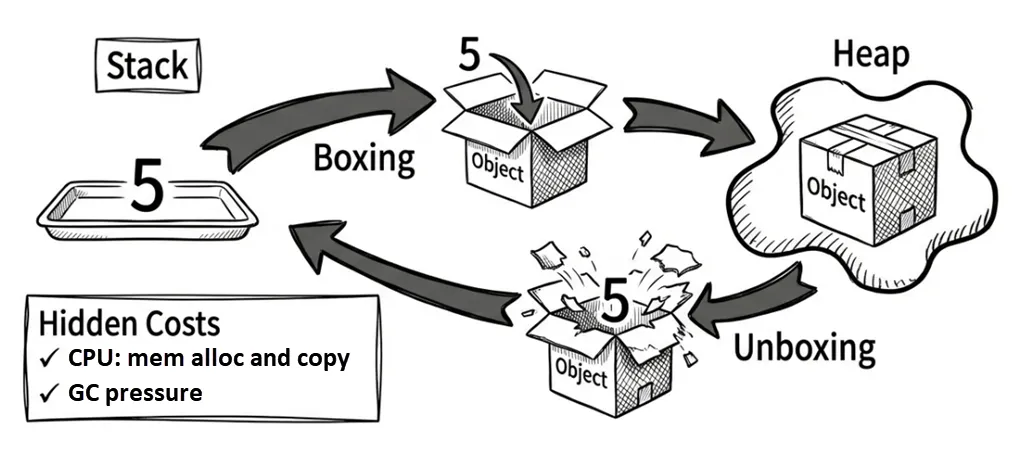

1.6 Boxing and unboxing

Boxing and unboxing are mechanisms that allow value types to be treated as objects, but they come with additional performance costs.

Boxing

Boxing is the process of converting a value type into an object (a reference type).

Imagine buying an apple (a value type). Normally, you can hold it in your hand (stack). But to store it in a warehouse (heap), you must place it in a box (boxing) and label it. Finding a box and packing the item is overhead.

What happens during boxing: the CLR allocates memory on the heap and copies the value-type data into it.

Example:

int i = 123;

object o = i; // Boxing: wraps the int in a heap-allocated objectUnboxing

Unboxing is the reverse process: converting an object back into a value type.

Unboxing involves verifying that the object contains the expected value type, then copying the value from the heap back to the stack.

Example:

int j = (int)o; // Unboxing

Why it matters

Boxing has two main costs:

- CPU work: Copying data and allocating memory.

- GC pressure: Boxing creates extra heap objects, giving the garbage collector more work.

Hidden boxing traps often show up in older collections (like ArrayList) or in string formatting:

int x = 10;

// Trap #1: string.Format takes object parameters

string s = string.Format("Score: {0}", x); // x gets boxed!

// Modern approach: string interpolation (often optimized by the compiler)

string s2 = $"Score: {x}";Source code: DemoBoxingUnboxing

Whether string interpolation causes boxing depends on the compiler version and the exact code. In modern C#/.NET, many common cases (such as interpolating an int) typically do not fall back to a string.Format(object, ...) path that boxes—though you can still incur string allocations.

If lots of formatted output sits on a hot path and you need high performance, more reliable approaches are:

- Avoid APIs that primarily take

objectparameters (for example, someparams object[]overloads). - Use

Span<T>to reduce string allocations (see Chapter 12). - For collections, prefer generic collections—for example, use

List<int>instead ofArrayList.

- String interpolation is introduced in Chapter 2 (Section 2.6).

- Generics are covered in Chapter 9.

1.7 Copying objects and arrays

When copying objects or arrays, you must understand shallow copy vs deep copy. C# does not provide a built-in deep-copy mechanism. This topic spans both value and reference types and is an important part of memory management.

Shallow vs deep copy for objects

A shallow copy copies only the object itself. Any reference-type fields inside still point to the same objects:

class Team

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public List<string> Members { get; set; }

// Uses object.MemberwiseClone() to copy members one by one (shallow copy)

public Team ShallowCopy() => (Team)MemberwiseClone();

}

var team1 = new Team

{

Name = "Dev",

Members = new List<string> { "Alice", "Bob" }

};

var team2 = team1.ShallowCopy(); // Shallow copy

team2.Name = "QA"; // team2 has its own Name value

team2.Members.Add("Charlie"); // But Members still points to the same List!

Console.WriteLine(team1.Members.Count); // Prints 3 (affected!)This shows a common shallow-copy bug: the inner reference object is not copied—only the reference is—so adding an element to team2.Members also mutates team1.Members.

Source code: DemoShallowCopy

Early .NET versions provided the ICloneable interface as a standard approach for object copying: implement Clone() and you’re done. The major downside is semantic ambiguity: Clone() doesn’t specify whether it returns a shallow or a deep copy. When you call a third-party Clone(), you often have to consult documentation to learn what it actually does. For shallow copies, the modern recommendation is to define an explicitly named method such as ShallowCopy, as shown above.

Note

Other ways to copy objects include a copy constructor, or using

recordtypes with thewithexpression (recommended; see Chapter 4).

What about deep copies? There are several approaches. The following example uses a copy constructor:

class Team

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public List<string> Members { get; set; }

public Team(Team original)

{

Name = original.Name; // string is immutable, so a shallow copy is fine

// Deep copy to avoid sharing the same reference

Members = new List<string>(original.Members);

}

}

var team1 = new Team

{

Name = "Dev",

Members = new List<string> { "Alice", "Bob" }

};

var team2 = new Team(team1); // Create a copy via the copy constructor

team2.Members.Add("Charlie");

Console.WriteLine(team1.Members.Count); // Prints 2 (team1 unaffected)Source code: DemoDeepCopy

In this example:

- The

Nameproperty is copied by reference (a shallow copy), but that’s fine becausestringis immutable. Even though strings look mutable, operations likeReplaceandToUppercreate new string objects. Membersis aList<string>, which is mutable. To avoid sharing the same list, you must create a new list instance.- A copy constructor is a best practice rather than a language mandate. The name is less explicit than

ShallowCopy/DeepCopy, but the benefits are strong typing (both input and output) and wide adoption in modern .NET. For example, C# 9recordtypes effectively provide compiler-generated copy constructors.

Note

recordtypes can also be combined with thewithexpression to easily perform shallow copies—this is the recommended approach in modern C#. See “Chapter 4: Immutable design.”

If an object contains nested reference types (for example, Team contains a Manager object, which contains other objects), a deep copy requires recursively creating new instances at every level. In practice, you can use serialization/deserialization (for example, System.Text.Json) or third-party libraries to automate deep copying.

Here’s a summary of common object-copy approaches:

- Implement

ICloneable.Clone(): obsolete and not recommended. Downsides: ambiguous semantics and not strongly typed (objectreturn type). - Copy constructor: commonly accepted best practice; recommended. Downside: verbose when there are many members.

record+with: concise syntax; recommended (Chapter 4).- Serialization: The simplest approach, but often slower and potentially misses private members.

Ask AI

I want to understand the pros and cons of these object-copy approaches in .NET: ICloneable, record (with), copy constructors, and serialization. Please summarize them in a comparison table.

Then, implement deep copy using .NET’s built-in

System.Text.Json.

Shallow vs deep copy for arrays

Array copying follows the same principle as object copying: Array.Clone() performs a shallow copy.

If the array element type is a value type (or string), a shallow copy is often enough:

int[] original = { 1, 2, 3 };

int[] copy = (int[])original.Clone();

copy[0] = 999;

Console.WriteLine(original[0]); // Prints 1 (unaffected; int is a value type)For reference-type elements, be careful:

var original = new StringBuilder[]

{

new StringBuilder("A"),

new StringBuilder("B")

};

var copy = (StringBuilder[])original.Clone();

copy[0].Append("!"); // Mutating copy also mutates original!

Console.WriteLine(original[0]); // Prints "A!" (affected!)To create a deep copy, you must copy each element individually:

var deepCopy = new StringBuilder[original.Length];

for (int i = 0; i < original.Length; i++)

{

deepCopy[i] = new StringBuilder(original[i].ToString());

}

deepCopy[0].Append("!");

Console.WriteLine(original[0]); // Prints "A" (unaffected)Source code: DemoDeepCopyArray

Summary

- C# design philosophy: An OOP + FP hybrid with strong type safety—let the compiler catch bugs.

- Execution model: Source compiles to IL, then the CLR uses JIT to produce machine code at runtime; the CLR also handles garbage collection (GC).

- Stack vs heap: The stack is fast but limited (mostly locals); the heap is large but GC-managed (object instances).

- Value types vs reference types: Value types contain data directly (copy by value); reference types store addresses (copy by reference).

- Array memory characteristics: Value-type arrays store elements contiguously (better locality); reference-type arrays store references (can increase GC pressure).

- Boxing/unboxing: Converting value types to

objectcan be a hidden performance trap; use generics to avoid it. - Object copying: C# provides shallow copy only; deep copy requires manual work or serialization (for example,

System.Text.Json).

In the next chapter, we’ll explore modern C# syntactic sugar and declaration techniques to help you write code that’s even cleaner and more expressive.

Buy now:

讀者互動